Chapter 21 Evil-designing men purchase deed to Smith property and press for immediate eviction of the Smiths. Mr. Durfee helps them, and they become tenants on their own land. Joseph’s and Hyrum’s marriages. Three-hour reprimand from Moroni to Joseph. The time is near for the plates to be received.December 1825 to spring 1827  Immediately after my husband’s departure, I set myself to work to put my house in order for the reception of my son’s bride. I felt that pride and ambition in doing this that is common to mothers upon such occasions. My oldest son, previous to this, had married a wife that was one of the most excellent of women, and I anticipated as much happiness with my second daughter-in-law, as I had received great pleasure from the society of the first. There was nothing in my heart which could give rise to any forebodings as to an unhappy connection. Immediately after my husband’s departure, I set myself to work to put my house in order for the reception of my son’s bride. I felt that pride and ambition in doing this that is common to mothers upon such occasions. My oldest son, previous to this, had married a wife that was one of the most excellent of women, and I anticipated as much happiness with my second daughter-in-law, as I had received great pleasure from the society of the first. There was nothing in my heart which could give rise to any forebodings as to an unhappy connection.

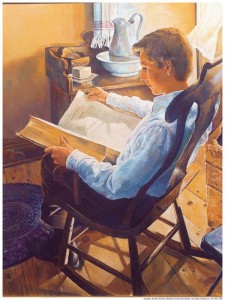

One very pleasant afternoon, immediately subsequent to this, being by myself and somewhat at leisure, having just finished arranging my house for the reception of my son and his bride, I looked around me upon the various comforts with which I found myself surrounded and which seemed to surpass our most flattering expectations, and I fell into a very agreeable train of reflections. I poured out my soul to God in thanks and praise for the many blessings which he had conferred upon us as a family. The day was exceeding fine and would of itself have produced fine feelings, but everything seemed to contribute to raise in the heart those soothing and grateful emotions that we all have reason to enjoy when the mind is at rest and the circumstances favorable. As I stood musing upon the busy, bustling life we had led, and the apparent prospect of a quiet and comfortable old age, my attention was suddenly attracted across the yard to a trio of strangers who were entering. Upon their nearer approach, I recognized Mr. Stoddard, the man who took charge of building the house that we now occupied. When they entered, I seated them and we commenced commonplace conversation, but one of them soon began to ask impertinent questions as to our making the last payment on the place and if we did not want to sell the house; where Mr. Smith and my son had gone; etc., etc. “Sell the house?” I replied. “No, sir, we have no occasion to sell the house. We have made every necessary arrangement for getting the deed and have an understanding with the agent, so we are quite secure about the matter.” To this they made no answer but went out to meet Hyrum, who was then coming in. They propounded the same questions to him and received the same answers. When they had experimented in this way to their satisfaction, they proceeded to inform my son that he need not put himself to any further trouble with regard to the farm, “for,” said they, “we have bought the place and paid for it, and we forbid you touching anything on the farm. Moreover, we warn you to leave forthwith and give possession to the lawful owners, as we have got the deed in our possession.” This conversation passed within my hearing. When they reentered the house, I said, “Hyrum, what does this mean? Is this a reality, or is it a sham to startle and deceive me?” One collected look at the men convinced me of their purpose. I was overcome and fell back into a chair, almost deprived of sensibility. When I recovered, Hyrum and I talked to them at length to reason them out of what they seemed determined to do, namely, to rush us out of our premises straightway into the common air like the beasts of the field or the fowls of heaven, with naught but the earth for a resting place and the canopy of the skies for a covering. But our only answer was, “Well, we’ve got the place, and d-m you, help yourselves if you can.” Hyrum went straightway to Dr. Robinson, an old friend of ours who lived in Palmyra and a man of influence and notoriety. He told the doctor the whole story. Then this gentleman sat down and wrote the character of my family, our industry and faithful exertions to obtain a home in the forest where we had settled ourselves, with many commendations calculated to beget confidence in us as to business transactions. This writing he took in his own hands and went through the village, and in an hour there was attached to the paper the names of sixty subscribers. He then sent the same by the hand of Hyrum to the land agent in Canandaigua. The agent was enraged when he found out the facts of the case. He said that the men told him that Mr. Smith and his son Joseph had run away and that Hyrum was cutting down the sugar orchard, hauling off the rails, burning them, and doing all possible manner of mischief to everything on the farm. Believing this, he had sold them the place, got his money, and given them a deed to the premises. Hyrum related the circumstances under which his father and brother had left home and also informed him that there was a probability of their being detained on the road on business. Hearing this, the agent directed him to write to his father by the first mail and have letters deposited in every public house on the road which Mr. Smith traveled. It might be that some of these letters would meet his eye and cause him to return more speedily than he otherwise would. The agent then dispatched a messenger to bring the men who had taken the deed of our farm, in order to make some compromise with them and, if possible, get them to relinquish their claim on the place. But they refused to come. The agent then sent another message to them, that if they did not make their appearance forthwith, he would fetch them with a warrant. To this they gave heed, and they came without delay. The agent used all the persuasion possible to convince them of the unjust, impolitic, and disgraceful measures which they had taken and urged them to retract from what they had done and let the land go back into Mr. Smith’s hands. But they were for a long time inexorable, answering every argument with taunting sneers like the following, “We’ve got the land, sir, and we have got the deed, so just let Smith help himself. Oh, no matter about Smith. He has gold plates, gold money; he’s rich. He don’t want anything.” At length, however, they agreed that if Hyrum could raise one thousand dollars by Saturday at ten o’clock in the evening, they would give up the deed. It was now Thursday near noon, and Hyrum was at Canandaigua, which was nine miles distant from home, and hither he must ride before he could make the first move towards raising the required amount. He came home with a heavy heart, supposing it impossible to effect anything towards redeeming the land, but when he arrived there he found his father, who had found one of the letters within fifty miles of home. The next day Mr. Smith requested me to go to an old gentleman who was a Quaker, a man with whom we had been intimate since our first commencement on the farm now in question, and who always admired the neatness and arrangement of the same. He had manifested a great friendship for us from our first acquaintance with him. We hoped that he would be able to furnish the requisite sum to purchase the place, that we might reap the benefit, at least, of the crops which were then sown on the farm. But in this we were disappointed, not in his will or disposition, but in his ability. This man had just paid out to the land agent all the money he could spare, within five dollars of his last farthing, in order to redeem a piece of land belonging to a friend in his immediate neighborhood. Had I arrived at his house thirty minutes earlier, I would have found him with fifteen hundred dollars in his pocket. When I told him what had occurred, he was much distressed for us and regretted having no means of relieving our necessity. He said, however, “If I have no money, I will try to do something for you. So, Mrs. Smith, say to your husband that I will see him as soon as I can and let him know what the prospects are.” It was near nightfall, the country new, and my road lay through a dense forest. I had ten miles to ride alone; however, I hastened to inform my husband of the disappointment. The old gentleman, as soon as I left, started in search of someone who could afford us assistance, and hearing of a Mr. Durfee, who lived four miles distant, he came the same night, and directed us to go and see what he could devise for our benefit. Mr. Smith went immediately and found Mr. Durfee still in his bed, as it was not light. He sent Mr. Smith still three miles further to his son, who was a high sheriff, and bid him say to the young man that his father wished to see him as soon as possible. Mr. Durfee, the younger, came without delay. After breakfasting, the three preceded together to the farm. It was now Saturday at ten o’clock a.m. They tarried a short time, and then rode on to meet the agent and our competitors. What I felt and suffered in that short day no one can imagine who has not experienced the same. I did not feel our early losses so much, for I realized that we were young and might by exertion better our situation. I, furthermore, had not felt the inconvenience of poverty so much as I had now done and consequently did not appreciate justly the value of property. I looked upon the proceeds of our industry, which smiled on every side of me, with a yearning attachment that I had never felt before. Mr. Smith and the Messrs. Durfee arrived at Canandaigua at half past nine o’clock in the evening. The agent immediately sent for Mr. Stoddard and his friends, who, when they came, averred that the clock was too slow, that it was really past ten. However, being overcome in this, they received the money and gave up the deed to Mr. Durfee, the high sheriff, who now came into possession of the farm. With this gentleman, we were now renters. Mr. Durfee gave us the privilege of the place for one year with this provision-that Samuel, our fourth son, was to labor for him six months. These things were all settled upon with the conclusion that if after we had kept the place in this way one year, we chose to remain, we still could have the privilege. Now Joseph, who had returned from his journey with his father, began to turn his mind again to what had occupied his attention previous to our disaster. He set out for Pennsylvania a second time and had such fine success that in January he returned in fine health and spirits. Soon after this, Mr. Smith had occasion to send Joseph to Manchester on business. He set out in good time, and we expected him to be home as soon as six o’clock in the evening, but he did not arrive. We had always had a peculiar anxiety about this child, for it seemed as though something was always occurring to place his life in jeopardy, and if he was absent one-half an hour longer than expected, we were apprehensive of some evil befalling him. It is true he was now a man, grown and capable of using sufficient judgment to keep out of common difficulties. But we were now aware that God intended him for a good and an important work; consequently we expected that the powers of darkness would strive against him more than any other, on this account, to overthrow him. But to return to the circumstances which I commenced relating. He did not return home until the night was considerably advanced. When he entered the house, he threw himself into a chair, seemingly much exhausted. He was pale as ashes. His father exclaimed, “Joseph, why have you stayed so late? Has anything happened to you? We have been in distress about you these three hours.” As Joseph made no answer, he continued his interrogations, until finally I said, “Now, Father, let him rest a moment-don’t trouble him now-you see he is home safe, and he is very tired, so pray wait a little.” The fact was, I had learned to be a little cautious about matters with regard to Joseph, for I was accustomed to see him look as he did on that occasion, and I could not easily mistake the cause thereof. After Joseph recovered himself a little, he said, “Father, I have had the severest chastisement that I ever had in my life.” My husband, supposing that it was from some of the neighbors, was quite angry and observed, “Chastisement indeed! Well, upon my word, I would like to know who has been taking you to task and what their pretext was. I would like to know what business anybody has to find fault with you.” Joseph smiled to see his father so hasty and indignant. “Father,” said he, “it was the angel of the Lord. He says I have been negligent, that the time has now come when the record should be brought forth, and that I must be up and doing, that I must set myself about the things which God has commanded me to do. But, Father, give yourself no uneasiness as to this reprimand, for I know what course I am to pursue, and all will be well.” It was also made known to him, at this interview, that he should make another effort to obtain the plates, on the twenty-second of the following September, but this he did not mention to us at that time. Back To Joseph Smith History Menu |