| Chapter 31 A group of religionists meets and plan to thwart the work of publishing the Book of Mormon. Mother Smith spends the night with the manuscript in a trunk under her bed. She contemplates many scenes she has passed through. Three men visit the Smiths with intentions of distracting Lucy, seizing the manuscript, and immediately burning it. Their scheme fails.

Early fall 1829

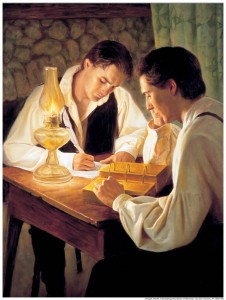

About the first council of this kind was held in a room adjoining that in which Oliver and young Mr. Robinson, son of our friend, Dr. Robinson, were printing. They suspected that something was agitated among these men that was not right, and Oliver proposed to Mr. Robinson that he should put his ear to a hole in the partition wall, and by this means he overheard the following remarks and resolutions: One said, “Now, gentlemen, this golden bible which the Smiths have got is destined to break down everything before it, if a stop is not put to it. This very thing is going to be a serious injury to all religious denominations, and in a little while, many of our excellent minister goodmen, who have no means of obtaining a respectable livelihood except by their ministerial labor, will be deprived of their salaries, which is their living. Shall we endure this, gentlemen?” Cries of “No! No!” “Well, how shall we put a stop to the printing of this thing?” It was then moved, seconded, and carried without a dissenting voice to appoint three of their company to come to our house on the following Tuesday or Wednesday, when the men were not about the house, and request me to read the manuscript to them; and that after I had done reading it, two of the company should attract my attention toward something else than the manuscript, and while they were doing this, the third should seize the writing from the drawer and throw the same into the fire and burn it up. “Again,” said the speaker, “suppose that we fail in this-or any other plan-and the book is published in defiance of all that we can do. What is then to be done? Shall we buy their books and suffer our families to read them?” They all responded, “No!” They then entered into a solemn covenant, binding themselves by tremendous oaths, that they would never own a single volume, nor would they permit one member of their families to do so, and thus they would nip the dreadful calamity while it was in the bud. Oliver came home that evening and related the whole affair with solemnity, for he was greatly troubled by it. “Mother, what shall I do with the manuscript? Where shall I put it to keep it away from them?” “Oliver,” said I, “do not think the matter so serious after all, for there is a watch kept constantly about the house, and I need not take out the manuscript to read it to them unless I choose, and for its present safety I can have it deposited in a chest, under the head of my bed, in such a way that it never will be disturbed.” I then placed it in a chest, raised up the head of my bedstead, and shoved the chest under it, letting the bedstead fall, so that the chest was securely closed, although it had neither lock nor key. At night we all went to rest at the usual hour except Peter Whitmer, who spent the night on guard. As for myself, soon after I lay down upon my bed, I fell into a train of reflections which occupied my mind until the day appeared. I called up to my recollection the past history of my life, and scene after scene seemed to rise in succession before me. The principles of early piety which were taught me when my mother called me, with my brothers and sisters, around her knee and instructed us to feel our constant dependence upon God, our accountability to him, our liability to transgression, the necessity of prayer, and of a death and judgment to come. Then again, I seemed to hear the voice of my brother Jason declaring to the people that the true religion and faith of the Church of Jesus Christ, which He established on the earth, was not among the Christian denominations of the day, and beseeching them, by the love of God, to seek to obtain that faith which was once delivered to the Saints. Again, I seemed to stand at the bedside of my sister Lovisa, and saw her exemplify the power of God in answer to the prayer of faith by an almost entire resuscitation, while her livid lips moved but to express one sentiment-which was the power of God over disease and death. The next moment I was conveyed to the closing scene of my sister Lovina’s life, and heard her last admonition to her mates and myself reiterated in my ear. Then my soul thrilled to the plaintive notes of the favorite hymn which she repeated in the last moments of her existence on earth. Oh, how often I had listened to the beautiful music of the voices of these two sisters and drunk in their tones as if I might ne’er hear them again. After that, I seemed to live again the season of gloominess, of prayers and tears, that preceded my sister’s death, when my heart was burdened with anxiety, distress, and fear lest I, by any means, should fail in that preparation which is needful in order to meet my sisters in that world for which they had taken their departure. It was then I began to feel the want of a living instructor in matters of salvation. How intensely I felt this deficiency when, a few years afterwards, I found myself upon the very verge of the eternal world; and although I had an intense desire for salvation, yet I was totally devoid of any satisfactory knowledge or understanding of the laws or requirements of that Being before whom I expected shortly to appear. But I labored faithfully in prayer to God, struggling to be freed from the power of death. When I recovered, I sought unceasingly for someone who could impart to my mind some definite idea of the requirements of heaven with regard to mankind. But like Esau seeking his blessing, I found them not, though I sought the same with tears. For days and months and years I continued asking God continually to reveal to me the hidden treasures of his will. Although I was always strengthened, I did not receive answer to my prayers for many years. I had always believed confidently that God would raise up someone who would effect a reconciliation among those who desired to do his will at the expense of all other things. But what was my joy and astonishment to hear my own son, though a boy of fourteen years of age, declare that he had been visited by an angel from heaven! My mind rested upon the hours which I had spent listening to the instructions which Joseph had received, and which he faithfully committed to us. We received these with infinite delight, but none were more engaged than the one from whom we were doomed to part, for Alvin was never so happy as when he was contemplating the final success of his brother in obtaining the record. And now I fancied I could hear him with his parting breath conjuring his brother to continue faithful that he might obtain the prize that the Lord had promised him. But when I cast my mind upon the disappointment and trouble which we had suffered while the work was in progress, my heart beat quickly and my pulse rose high, and in my best efforts to the contrary, my mind was agitated. I felt every nervous sensation which I experienced at the time the circumstances took place. At last, as if led by an invisible spirit, I came to the time when the messenger from Waterloo informed me that the translation was actually completed. My soul swelled with a joy that could scarcely be heightened, except by the reflection that the record which had cost so much labor, suffering, and anxiety was now, in reality, lying beneath my own head-that this identical work had not only been the object which we as a family had pursued so eagerly, but that prophets of ancient days, angels, and even the great God had had his eye upon it. “And,” said I to myself, “shall I fear what man can do? Will not the angels watch over the precious relic of the worthy dead and the hope of the living? And am I indeed the mother of a prophet of the God of heaven, the honored instrument in performing so great a work?” I felt that I was in the purview of angels, and my heart bounded at the thought of the great condescension of the Almighty. Thus I spent the night surrounded by enemies and yet in an ecstasy of happiness. Truly I can say that my soul did magnify and my spirit rejoiced in God, my Savior. On the fourth day after they had met, the three men delegated by the council came to perform the work assigned them. They began, “Mrs. Smith, we hear you have a gold bible, and we came to see if you would be so kind as to show it to us?” “No, gentlemen,” said I, “we have no gold bible, but we have a translation of some gold plates, which have been brought forth to bring to the world the plainness of the gospel and to give to the children of men a history of the people that used to inhabit this continent.” I then proceeded to give them the substance of what is contained in the Book of Mormon, particularly the principles of religion which it contains. I endeavored to show them the similarity between these principles and the simplicity of the gospel taught by Jesus Christ in the New Testament. “But,” added I, “the different denominations are very much opposed to us. The Universalists come here wonderfully afraid that their religion will suffer loss. The Presbyterians are frightened lest their salary will come down. The Methodists come and they rage, for they worship a God without body or parts, and the doctrine we advocate comes in contact with their views.” “Well,” said the foremost gentleman with whom I was acquainted, “can we see the manuscript?” “No, sir, you cannot see it. We have done exhibiting the manuscript altogether. I have told you what is in it, and that must suffice.” He did not reply to this, but said, “Mrs. Smith, you, Hyrum, Sophronia, and Samuel have belonged to our church for some time, and we respect you very highly. You say a great deal about the book which your son has found and believe much of what he tells you, but we cannot bear the thoughts of losing you, and they do wish-I wish-that if you do believe those things, you never would proclaim anything about them. I do wish you would not.” “Deacon Beckwith,” said I, “even if you should stick my body full of faggots and burn me at the stake, I would declare, as long as God should give me breath, that Joseph has that record, and that I know it to be true.” He then turned to his companions and said, “You see, it is no use to say anything more to her, for we cannot change her mind.” Then, addressing me, he said, “Mrs. Smith, I see that it is not possible to persuade you out of your belief, and I do not know that it is worthwhile to say any more about the matter.” “No, sir,” said I, “it is of no use. You cannot affect anything by all that you can say.” He then bid me farewell and went out to see Hyrum, when the following conversation took place between them: Deacon Beckwith: “Mr. Smith, do you not think that you may be deceived about that record which your brother pretends to have found?” Hyrum: “No, sir, I do not.” Deacon Beckwith: “Well, now, Mr. Smith, if you find that you are deceived, and that he has not got the record, will you confess the fact to me?” Hyrum: “Will you, Deacon Beckwith, take one of the books, when they are printed, and read it, asking God to give you an evidence that you may know whether it is true?” Deacon Beckwith: “I think it beneath me to take so much trouble; however, if you will promise that you will confess to me that Joseph never had the plates, I will ask for a witness whether the book is true.” Hyrum: “I will tell you what I will do, Mr. Beckwith, if you do get a testimony from God that the book is not true, I will confess to you that it is not true.” Upon this they parted, and the deacon next went to Samuel, who quoted to him Isa. 56:9-11: “All ye beasts of the field, come to devour, yea, all ye beasts in the forest. His watchmen are blind: they are all ignorant, they are all dumb dogs, they cannot bark; sleeping, lying down, loving to slumber. Yea, they are greedy dogs which can never have enough, and they are shepherds that cannot understand: they all look to their own way, every one for his gain, from his quarter.” Here Samuel ended the quotation, and the three gentlemen left without ceremony. Back To Joseph Smith History Menu |